Edvard

Grieg -- Exponent of creative piano chords

Edvard

Grieg -- Exponent of creative piano chords

"I am not an exponent of

'Scandinavian Music' but only of Norwegian. The national characteristics of

the three peoples - the Norwegians, the Swedes and the Danes - are wholly

different, and their music differs as much." Edvard Grieg

Grieg's strong national tendencies,

despite his conventional German training, places him at once in a class with

Dvorak, Rimky-Karsakov and others who have attempted to preserve the beautiful

spirit embedded in the folk music of the lands of their birth. "The Land

of the Midnight Sun" presents many of the most strongly pronounced

national characteristics to be found in any part of Europe. The location and

topography of the country has much to do with this. In the same latitude as

Greenland and spared the same icy fate by the Gulf Stream, Norway reaches from

a temperate climate right up into the frozen north. Its west coast is a huge

series of natural parapets broken by fjords sometimes a hundred miles in

length and thousands of feet in depth. It is not surprising that a land so

situated should hold its people together in wonderfully strong natural bonds.

Although Grieg was born when Norway was a part of Sweden he always made a

strong distinction between the two countries.

Norway became part of Sweden in 1814,

and it was not until the bloodless revolution of 1905 that Norway regained her

national integrity. Grieg himself was one of the leaders in the great

intellectual and educational awakening of the country. Bjornssen, Ibsen,

Svendsen, Ole Olsen, Halvorson and others all felt the spirit of re-birth

which was stimulating their native land, and these men were majestic enough to

realize that the true sovereignty of the Norway of the future must depend upon

the perpetuation of the wonderful spirit of the Norwegians of the past. Thus

Ibsen in his plays aimed to preserve the Norwegian spirit but not without

criticising the Norwegian of the present day, when it is evident that he was

forsaking the ideals of the homeland. This ibsen did in a marvelous manner in

his romantic play Peer Gynt, to which Grieg has set such beautiful

music. It was not surprising that Grieg was influenced by the great

intellectual activity about him. Fortunately he realized at a very early age

this his greatness depended upon his loyalty to the spirit of his native land.

Otherwise he might have been a repetition of Gade, music, able, and

academically proficient, but writing in a tongue other than his own.

Grieg's

Ancestry

Grieg's

Ancestry

In 1745-1746, the Pretender, Charles

Edward Stuart, attempted to re-establish himself in Scotland.

Overwhelmed by numbers and superior arms

the Highlanders succumbed to the English soldiers at the battle of Culloden.

Those who were taken prisoners were either hung or transported. Alexander

Grieg, a merchant of Aberdeen, was one of those driven out. He found a haven

in Bergen, Norway, where he determined to settle. In order to facilitate

pronunciation he changed his name from Greig to Grieg. His grandson Alexander

Grieg married Gesine Judith Hagerup, and their son was none other than Edvard

Grieg, the greatest master of music Norway has produced. His father, a highly

cultured and sympathetic man, was not especially musical. His mother, however,

was a musician of decided ability not only as a pianoforte soloist but as a

composer of attractive folk songs constructed of colorful broken piano chords,

some of which are said to retain their popularity still in Norway.

Grieg's Birthplace

Grieg was born at Bergen, June 15, 1843.

The city of his birth apart from its inspiring natural location is one of the

great intellectual centers of Europe.

It has been said that a finer spirit of

culture and pure democracy exists in Bergen than in any other old world city.

Grieg's Early Training

Naturally Grieg's first instruction came

from his mother. His lessons started at the age of six. Possibly more

important even than the regular piano lessons was the fact that he had the

advantage of hearing his mother play continuously. There were weekly musicals

in the home, and everything possible was done to encourage the talent of the

child which even at that time was manifest. The mother was by no means a

lenient teacher. She insisted that he learn chords -- specifically, piano

chords. Energetic and clear-headed she insisted upon having her boy practice

things that were unpleasant to him as well as those which were pleasant.

At the age of twelve or thirteen he

commenced to compose, much to the disgust of his teachers who regarded such

youthful "indiscretions" as rubbish. Grieg had a distaste for

everything that savored of the didactic or academic. Accordingly his school

days were made very miserable to him by his materialistic teachers.

His first ambition, however, was to be a

preacher, and he loved to declaim imaginary sermons to members of his family.

At the age of fifteen Grieg met that remarkable Norwegian musician and

patriot, Ole Bull, who immediately took a great interest in the boy. It was

through his influence that Grieg's parents were induced to send their talented

son to the Leipsig Conservatory. At the age of fifteen Grieg met that

remarkable Norwegian musician and patriot, Ole Bull, who immediately took a

great interest in the boy. It was through his influence that Grieg's parents

were induced to send their talented son to the Leipzig Conservatory.

The Influence of Leipzig

The change from the gloriously romantic

surroundings of Bergen to the prosaic environment of Germany's great

commercial center, Leipzig, must have had a peculiar effect upon a youth as

sensitive as Grieg. Although the city still retained some of its medieval

aspects at that time (1858), it was vastly different from the Bergen of the

same period. Moscheles, Richter, Hauptmann, Wenzel, Reinecke and Plaidy were

Grieg's teachers at Leipzig. Grieg worked very industriously. Indeed he

suffered a breakdown in 1860, due to working night and day for months at a

time. The policy of the conservatory at that time was repression rather than

progress.

Plaidy,

Richter and even Moscheles were men who sought to put their pupils ahead by

holding them back through interminable technical contrivances. Grieg entered

heartily into all the work that he did, but in after years he berated some of

the Leipzig teachers very severely for not appreciating his natural talent and

developing it along more rational lines. A little later Grieg met Gade whom he

admired greatly. Gade had forsaken his national idols with the view of

procuring an international audience. In other words, he preferred to be more

universal in his appeal. Fortunately, through the friendship of staunch

Norwegians, Grieg was shown the path which later led him to such vast renown.

By this, however, the reader should not infer that Grieg could not write in a

manner which appeals to the so-called "universal audience." Indeed

there are numerous compositions of Grieg which show but very slight trace of

the Norwegian.

Plaidy,

Richter and even Moscheles were men who sought to put their pupils ahead by

holding them back through interminable technical contrivances. Grieg entered

heartily into all the work that he did, but in after years he berated some of

the Leipzig teachers very severely for not appreciating his natural talent and

developing it along more rational lines. A little later Grieg met Gade whom he

admired greatly. Gade had forsaken his national idols with the view of

procuring an international audience. In other words, he preferred to be more

universal in his appeal. Fortunately, through the friendship of staunch

Norwegians, Grieg was shown the path which later led him to such vast renown.

By this, however, the reader should not infer that Grieg could not write in a

manner which appeals to the so-called "universal audience." Indeed

there are numerous compositions of Grieg which show but very slight trace of

the Norwegian.

Northern Lights

It was to Ole Bull and Rikard Nordraak

that Grieg owed his reclamation from the conventional to the highly flavored

folk music of Norway. With Ole Bull he traveled over mountain after mountain

becoming better and better acquainted with the music of his homeland. Nordraak,

although he died before he became twenty-four, and although the greater part

of his fame rests upon his association with Grieg, was a remarkable force as a

patriot and as a musician. Side by side they worked to foster Norwegian music,

and it was to such spirits as Nordraak that Grieg repaired when he received

communications from Gade advising his (Grieg) to make his next work less

Norwegian.

Grieg's

Road to Success

Grieg's

Road to Success

In 1867, Grieg married Nina Hagerup, a

most felicitous union. Mme. Grieg, although a cousin to her husband, was a

Dane. She possessed such splendid talent as a singer that her husband was

immensely helped by her loving assistance. Their only child, a daughter, died

at the age of thirteen months. The Griegs lived in Christiana for eight years

where Edvard was the conductor of the thriving Philharmonic Society, and where

they met another remarkable Norwegian couple, the Bjornsons. By this time

Grieg had produced some of his most significant works, including the

remarkable Violin Sonata, Opus 8, and the Piano Sonata, Opus 7. Liszt took a

great interest in the Opus 8, and wrote the twenty-five-year-old composer a

letter so eulogistic that the Norwegian government granted Grieg a sufficient

sum of money to enable him to visit Rome again.

When Grieg reached Rome he naturally

sought out Liszt at once. The old master greeted the young composer with his

usual warmth and cordiality. Grieg has some manuscript compositions with him

and played them, much to the delight of the great pianist. It is interesting

to note that the piano upon which this historical performance was given was of

American make. Piano chords sounded wonderfully full on this instrument.For a

time they played the Norwegian composer's violin Sonata, Liszt playing the

solo part upon the upper octaves of the piano with what Grieg described as

"an expression so beautiful, so marvelously true and singing that it made

me smile inwardly." Then Liszt played for Grieg part of his symphonic

poem, Tasso: Lamento e Trionfo. After this Liszt played a violin

sonata of Grieg from manuscript at sight, playing both the violin and the

piano parts as though it were one composition, and even broadening out the

work here and there according to his own ideas.

A Famous Compositon

Ibsen, the greatest dramatic genius

since Shakespeare, invited Grieg to write music for his wonderful idealistic

portrait of an imaginary Norwegian character, Peer Gynt. The drama was

first produced in February, 1876, and was a pronounced success. The only

American performances of not were those given by the late Richard Mansfield,

to whom great credit must be given for accomplishing a most intricate and

praiseworthy artistic undertaking. The Grieg music, however, has become among

the most popular of the world's musical classics.

Grieg's Later Years

In 1877 Grieg returned to his native

land and built a small study-house on one of the gorgeously beautiful fjords

near the Hardanger Fjord. There, in a little one-room study, Grieg wrote many

of his most beautiful things. This little house soon became the Mecca for so

many visitors that in 1855 he abandoned the plan and built the villa

Troldhaugen (hill of the sprites), which remained his home until his death.

This was located a few miles from Bergen. Grieg made frequent visits to the

continent for the purpose of introducing his compositions. Everywhere he was

received with great favor. In 1888, he played his pianoforte concerto in

London with the Philharmonic Orchestra, and thereafter made additional trips

to England where both he and his wife became very popular. In 1894, Cambridge

University gave him the honorary degree of Doctor of Music. Grieg was often

invited to come to America by managers who had not been slow to observe the

enormous success of his European appearances. Shortly before death, one

American manager sent him a pressing invitation to make a tour of this

country. Grieg replied that owing to his very frail health he had always

avoided the trip, but suggested that if he could be guaranteed thirty concerts

at two thousand five hundred a concert he would make the attempt. Of course

this amount was prohibitive. From this it would appear that Grieg was a good

business man. In a sense, he was, be he estimated that the total earnings of

all his compositions received by him during his entire lifetime was not equal

to the royalties upon the Merry Widow during the performance of that

opera in the city of Christiana alone.

In his later years Grieg was a continual

sufferer from asthma. In August 1907, the effects of the disease became more

and more noticeable. He was obliged to go to a hospital. He realized that the

end was near and died during the night of September 3rd. An autopsy revealed

that his sufferings for years had been excruciating. He was so deeply loved by

the Norwegian people that his death fairly staggered the nation. The funeral

was conducted by the Norwegian government, and took place in part in the

leading art museum of Bergen. Fifty thousand people were in the vast throng

which sought to attend the funeral. Floral tributes came from all over Europe,

including a wreath sent by the German Kaiser. Grieg's remains were cremated

and buried in the side of a precipice near Troldhaugen.

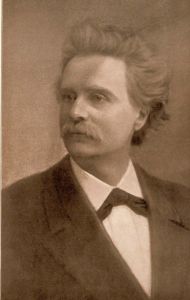

Grieg's Personality and Appearance

Grieg's appearance was very striking

despite the fact that he was not tall. He wore his hair long. It was straight

and very nearly white at an early age. His eyes were blue and very

intelligent. The fact that he had asthma gave him a tendency to stoop. Grieg

had a charming personality, genial, keenly intelligent, simple and

enthusiastic. He naturally had many friends. He was extremely modest. He

talked much of piano chords and their character.Tchaikavski described his

glance as that of one recalling a charming and candid child.

Grieg as a Performer

Frank Van der Stucken gave Mr. Henry T

Finck the following account of Grieg's art as a performer. "As a

performer, Grieg is the most original I ever heard. Though his technic

suffered somewhat from the fact that a heavy wagon crushed one of his hands,

and that he lost the use of one of his lungs in his younger days, he has a way

of performing his compositions that is simply unique. While it lacks the

breadth that a professional virtuoso infuses in his work, he offsets this by

the most poetic conception of piano chords & lyric parts and a wonderfully

crisp and buoyant execution of the rhythmical passages."

Grieg's Public Work

Grieg's naturally delicate constitution

and nervous temperament prevented him from doing as much concert work as he

would have done had he been a robust man. Dr. Edward Hanslick, the noted

Vienese critic, said of his performances, "His piano playing is

enchantingly tender and elegant, and at the same time entirely individual. He

plays like a great composer who is thoroughly at home at the piano, neither

being its tyrant nor its slave - not like a traveling virtuoso who also

devotes some attention to composing. His technic is at the same time flawless,

well groomed and smooth. Grieg need not fear to enter the lists against many a

virtuoso; but he contents himself with the finished execution of lyrical

pieces and dispenses with capering battle horses."

Those who heard Grieg play such pieces

as his Butterflies and To Spring have said that he seemed to

create an atmosphere about them that was like the humming of bees or the

gentle wafting of zephyrs. Once the piece was started, it seemed to rise in

the atmosphere like a bird, and soar gently but surely, never alighting until

the end. When he played in London crowds gathered around the doors as early as

eleven o'clock in the morning and waited until their opening in the evening.

There was only one Grieg and they were not going to miss hearing him.

What Tchaikovsky Thought of Grieg

The great Russian master was one of the

most enthusiastic admirers of Grieg. He delighted to read his music and felt

that each piece contained some new and characteristic message. He said,

"Hearing the pieces of Grieg we instinctively recognize that it was

written by a man impelled by an irresistible impulse to give vent by means of

sounds to a poetical emotion, which obeys no theory or principle, is stamped

with no impress but that of vigorous and sincere artistic feeling. Perfection

of form, strict and irreproachable logic in the development of his themes are

not perseveringly sought after by the Norwegian master. But what grace, what

inimitable and rich musical imagery. What warmth and passion in his melodic

passages, what teeming vitality in his harmony, what originality and beauty in

the turn of his piquant and inglorious modulations and rhythms, and in all the

rest what interest, novelty and independence! If we add to all this that

rarest of qualities, a perfect simplicity far removed from all affectation and

pretence to obscurity and far-fetched novelty, etc., etc."

"I trust that it will not appear

like self-glorification that my dithyramb in praise of Grieg precedes the

statement that our natures are closely allied. Speaking of Grieg's high

qualities, I do not at all wish to convey the idea that I am endowed with an

equal share of them. I leave it to others to decide how far I am lacking in

all that Grieg possesses in such abundance, but I cannot help stating the fact

that he exercises, and has exercised, some measure of that attractive force

which always drew me toward the gifted Norwegian."

Books About Grieg

The books about Grieg are comparatively

few, although there are numerous magazine articles and contributions to

collective biographical works. Daniel Gregory Mason's From Grieg to Brahms,

and E. Markham Lee's Grieg were the best works upon the composer until

the appearance of the incomparable biography of Mr. H T Finck, the well-known

American critic who knew Grieg well, and who corresponded with him frequently

during the preparation of Grieg and His Music. This is one of the most

interesting and instructive works of its kind, and has been used as the basis

for much of the present monograph.

Grieg's Compositions

Grieg had the delightful faculty of

expressing his thoughts with harmonies refreshingly new and often exceedingly

original. Many of his themes have been traced indisputably to Norwegian fold

music sources, but it remained for Grieg to supply the harmonic background

through which these compositions might be presented to the world in all their

delicious verity of Norse flavor. He expanded the resources of harmonic usage

far more than those of his own time realized. Twenty-six of Grieg's opus

numbers are for piano solo. Many of these opus numbers include collections of

numerous short piano pieces. His best known orchestral works Before the

Cloister Gate, Landsighting, and Olaf Trygvason are perhaps

the most popular. Of Grieg's one hundred and twenty-five songs only a very few

have become popularly known. Of these Ich Leibe Dich, The Swan Song

and Solveig's Lied are the most liked. It may be noticed that here is a

composer who has written no symphonies nor any operas yet one who ranks with

the foremost masters. Illness prevented him from becoming a dramatic composer.

The Etude

Magazine June 1911

Edvard

Grieg -- Exponent of creative piano chords

Edvard

Grieg -- Exponent of creative piano chords Grieg's

Ancestry

Grieg's

Ancestry

Plaidy,

Richter and even Moscheles were men who sought to put their pupils ahead by

holding them back through interminable technical contrivances. Grieg entered

heartily into all the work that he did, but in after years he berated some of

the Leipzig teachers very severely for not appreciating his natural talent and

developing it along more rational lines. A little later Grieg met Gade whom he

admired greatly. Gade had forsaken his national idols with the view of

procuring an international audience. In other words, he preferred to be more

universal in his appeal. Fortunately, through the friendship of staunch

Norwegians, Grieg was shown the path which later led him to such vast renown.

By this, however, the reader should not infer that Grieg could not write in a

manner which appeals to the so-called "universal audience." Indeed

there are numerous compositions of Grieg which show but very slight trace of

the Norwegian.

Plaidy,

Richter and even Moscheles were men who sought to put their pupils ahead by

holding them back through interminable technical contrivances. Grieg entered

heartily into all the work that he did, but in after years he berated some of

the Leipzig teachers very severely for not appreciating his natural talent and

developing it along more rational lines. A little later Grieg met Gade whom he

admired greatly. Gade had forsaken his national idols with the view of

procuring an international audience. In other words, he preferred to be more

universal in his appeal. Fortunately, through the friendship of staunch

Norwegians, Grieg was shown the path which later led him to such vast renown.

By this, however, the reader should not infer that Grieg could not write in a

manner which appeals to the so-called "universal audience." Indeed

there are numerous compositions of Grieg which show but very slight trace of

the Norwegian.

Grieg's

Road to Success

Grieg's

Road to Success